Unit Economics of a Marketplace: CAC, Margin, and Break-Even Point Using Niche E-Commerce as an Example

If you’ve ever watched a tight community rally around a hobby—think dartboards, flights, and team shirts—you’ve already seen how niche demand takes shape. Fans who track odds on sportsbooks with darts tend to buy repeatedly and recommend gear to friends. That same loyalty is what makes unit economics for a niche e-commerce marketplace both tractable and testable: you can measure the cost of getting one buyer, the cash you keep on every order, and how long it takes to earn back acquisition spend.

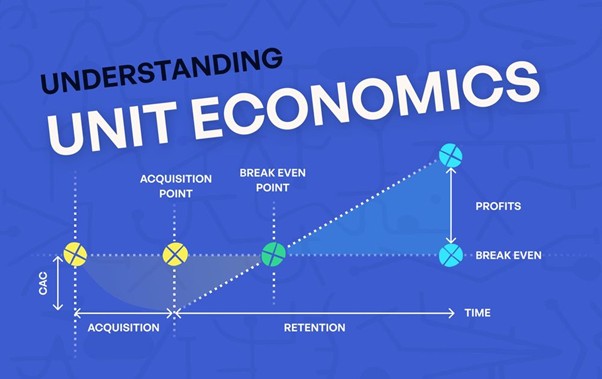

Before we work through numbers, set the “unit.” In a two-sided marketplace, your unit is usually a completed order on the buyer side; revenue flows from a commission (“take rate”), listing fees, or fulfillment services. Everything you calculate—CAC (customer acquisition cost), contribution margin, and payback—should trace back to this single transaction. With that lens, the math stays consistent whether you sell dart flights or hand-cast soap.

CAC in a niche marketplace: realistic math, not wishful thinking

Marketing teams love channel dashboards; finance teams love cash payback. Unit economics asks both groups for one answer: “What did it cost to acquire a new buyer who actually converted?” In a niche marketplace, CAC tends to be lower than in mass retail because keywords are specific, communities are organized, and content converts if it solves real problems (e.g., “best steel-tip darts for small rooms”). Still, it’s easy to undercount hidden costs like creative production or promotional credits.

Below is a sample CAC breakdown for a darts-gear marketplace acquiring hobbyists in the U.S. Numbers are illustrative, but the structure is universal.

| Line item | Basis | Monthly spend | New buyers from channel | CAC per new buyer |

| Paid search (long-tail keywords) | CPC | $9,000 | 300 | $30.00 |

| Social ads (interest bundles) | CPM/CPC | $6,000 | 160 | $37.50 |

| Influencer seeding (micro-creators) | Flat + product | $3,000 | 120 | $25.00 |

| Affiliate (content/review sites) | Rev-share + flat | $2,800 | 90 | $31.11 |

| Content/SEO (editor + tools)* | Salaries/retainers | $4,200 | 140 | $30.00 |

| Email/SMS capture (pop-ups, lead gen)** | Tools + promos | $1,500 | 80 | $18.75 |

| Weighted total | $26,500 | 890 | $29.78 |

* Attribute SEO by new organic buyers added that month; longer arcs require cohort modeling.

** Only count buyers whose first purchase started in the same period due to your capture tactics.

Takeaway for CAC: You don’t have one number—you have a mix that changes with creative fatigue, seasonality, and keyword auctions. The working CAC you model for payback should be your weighted figure for the most recent stable month, with sensitivity ±15% to catch volatility. And be honest about promo credits: if the first order uses a $5 coupon, that is part of acquisition, whether you book it in marketing or not.

Margin and break-even: from order #1 to cash payback

Once you trust CAC, you need the contribution you earn on each order to see how fast you get your money back. In a marketplace, the most common revenue stream is a commission (take rate) on GMV. Some marketplaces also charge payment, protection, or fulfillment fees to sellers—or bundle logistics and keep a service margin. The trick is to separate variable costs (scale with orders) from fixed costs (don’t scale directly with each order) and model payback using contribution margin after variable costs but before overhead.

Here’s how to build it step by step:

- Define per-order revenue.

If average order value (AOV) is $60 and your commission is 15%, revenue per order is $9. If you also keep $1 per label for shipping coordination, revenue is $10. - Subtract variable costs tied to that order.

Think payment processing (2.9% + $0.30 ≈ $2.04 on $60), fraud loss reserve (say 0.3% of GMV = $0.18), buyer support ($1 per ticket blended), and promo credits used on first orders ($5 coupon if you’re using them to kickstart conversion). On first orders, variable costs might total $8.22; on repeat orders (no coupon), closer to $3.22. - Get contribution margin per order.

First order: $10 revenue − $8.22 costs ≈ $1.78.

Repeat order: $10 − $3.22 ≈ $6.78. - Translate margin into payback against CAC.

With a weighted CAC of ~$30, you’ll need ~17 first-order equivalents to break even—not realistic. But your real mix is one first order and several repeats. Using the margins above, you might need one first order plus about five repeat orders to cover $30 (1.78 + 5×6.78 = $35.68). If your average repeat cadence is six weeks, payback would occur around month 7–8. - Improve levers that move both sides.

Tiny changes compound: a 1-point take-rate increase, lower refund rate, or cheaper payments (say, ACH for U.S. subscriptions) can shave a month from payback, while a better onsite quiz can grow AOV to $70, adding $1–$2 contribution per order.

Why this matters: Cash payback governs how fast you can grow without constant external funding. If payback slips past 12 months, acquisition becomes a strain and retention has to carry the story. If you bring it under six months, you can recycle cash sooner and expand channels with confidence.

A worked “darts marketplace” example you can sanity-check

Let’s thread the numbers together so you can see the moving parts in one place.

- AOV: $60

- Take rate: 15% + $1 logistics fee → $10 revenue per order

- Variable costs, first order: payments $2.04 + fraud reserve $0.18 + support $1 + coupon $5 = $8.22

- Variable costs, repeat: payments $2.04 + fraud $0.18 + support $1 = $3.22

- Contribution margin: first order $1.78; repeat $6.78

- Weighted CAC: ~$30

- Repeat rate: 40% of buyers place 2.1 additional orders over six months (average repeat cadence ~6 weeks)

- Refund/return rate: 4% of GMV, already absorbed in the fraud/adjustment reserve above (if your vertical has sizing issues, explicitly model returns).

With that mix, the median buyer places ~3 orders in six months (1 initial + ~2 repeats). Contribution in that window is $1.78 + 2×$6.78 = $15.34—short of CAC. However, your retained cohort (the 40%) keeps ordering. If they average 4–5 total orders in a year, contribution per retained buyer lands in the $29–$36 range, which gets you near or past cash payback by month 7–9. The business then earns real profit only if retention stretches beyond one year or if you increase per-order contribution.

Key point: When teams speak about “LTV,” keep it grounded in time-boxed, observed cohorts. Twelve-month contribution divided by CAC is a better operating ratio than a theoretical lifetime value stretched over years.

The two levers that change everything (and how to move them)

You don’t need a hundred tactics—just two compounding levers: raising contribution per order and dropping CAC without hurting quality. Here’s a short checklist that focuses on durable moves rather than channel hacks:

- Grow AOV with real value. Bundles (e.g., “starter set: board + flights + oche”) and post-purchase add-ons beat blanket coupons. Even $5 AOV lift adds ~$0.75–$1 contribution per order at a 15% take rate.

- Trim variable costs. Negotiate payment fees at volume tiers; add ACH/Wallets for frequent buyers; build a self-serve sizing/fit Q&A to shrink ticket load.

- Reduce coupon exposure on first purchase. Swap $5 off for free shipping thresholds or loyalty points that trigger on order two.

- Lift take rate via services. Offer seller-paid badge placement, insurance, or managed fulfillment for a fee—each raises per-order revenue without new buyers.

- Target higher-intent traffic. Niche search terms, community forums, and creator reviews close better than broad social. CAC drops when pre-qualified customers arrive already wanting a specific SKU.

- Retain with post-purchase value. Email the life of consumables (grip wax, replacement flights), set reminders, and reward streaks. Repeat orders at $6–$7 contribution are your compounding engine.

What this yields: If you lift per-order contribution from $6.78 to ~$8 on repeats and nudge AOV from $60 to $66, the same buyer with four orders in a year contributes ~$1.78 + 3×$8.00 = $25.78 in year one; five orders put you over $33. Combine that with a CAC that slides from $30 to $26 as you tune channels, and cash payback pulls forward by one to two months.

Common pitfalls that distort unit economics

Even seasoned teams slip on a few recurring issues. Keep an eye on these, because each one makes CAC look prettier than it really is or margin look fatter than it truly is.

- Counting “new” buyers who already bought under a different email or through a marketplace partner.

- Treating coupon cost as a top-line discount rather than as part of acquisition.

- Ignoring partial refunds, disputes, and reshipments in variable costs.

- Modeling LTV on gross revenue instead of contribution margin.

- Averaging AOV across all orders without segmenting by first vs. repeat.

Repair strategy: Build reports that lock to cohorts by first order month, show contribution at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, and display CAC and payback windows for the same cohorts. Finance owns the template; marketing and product own the improvements.

Final thought

Unit economics is not an academic exercise; it’s the cash rhythm of your marketplace. Start with a clean unit (one order), pin down a weighted CAC that reflects how you truly spend to win a buyer, and make each order worth a little more while keeping variable costs tight. In a focused niche like darts, you’re rewarded twice: acquisition stays targeted, and retention rides the calendar of leagues, seasons, and small upgrades. When those two forces align, payback speeds up, and growth becomes a habit—not a hope.