TEDDINGTON AT WAR – LEST WE FORGET

Teddington Town is commemorating Remembrance Sunday this year with a series of articles about Teddington and its historic links to wartime.

Teddington Town is commemorating Remembrance Sunday this year with a series of articles about Teddington and its historic links to wartime.

Many locals will be familiar with the history which includes Bushy Park being turned into a vital US military base in the run up to the D-Day landings in 1944 and the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) being targeted by the Luftwaffe as well as losing key staff in the bombings.

This year’s Remembrance events appears to be more poignant than ever with the latest conflict in Israel and Gaza and the ongoing war between Russian and Ukraine and reminds us of those who fought and gave their lives for our freedom.

The UK military and its Armed Forces is playing a massive supportive role and thousands of UK troops are deployed overseas in a protective role and we should recognise, perhaps more than ever, their vital contribution to keeping us safe and secure.

Historic records show that local war memorials list 159 local servicemen and women and 96 civilians who died during the air raids in and around Teddington or due to other enemy action between September 1939 and August 1945.

On one devastating night, November 29th1940 Teddington sustained its highest casualties with 74 people killed in an attack involving 130 bombs and between 3,000 and 5,000 incendiary devices raining down on Twickenham and Teddington, destroying 150 houses and damaging more than 6,000 others.

The worst damage was sustained in Church Road, Teddington but entire families were wiped out in Railway Road and Shacklegate Lane including young children.

In a series of articles in the run up to Remembrance Sunday we will look back at Teddington during those war years. In this first piece local historian gives an overview of how WW11 affected our town and homes.

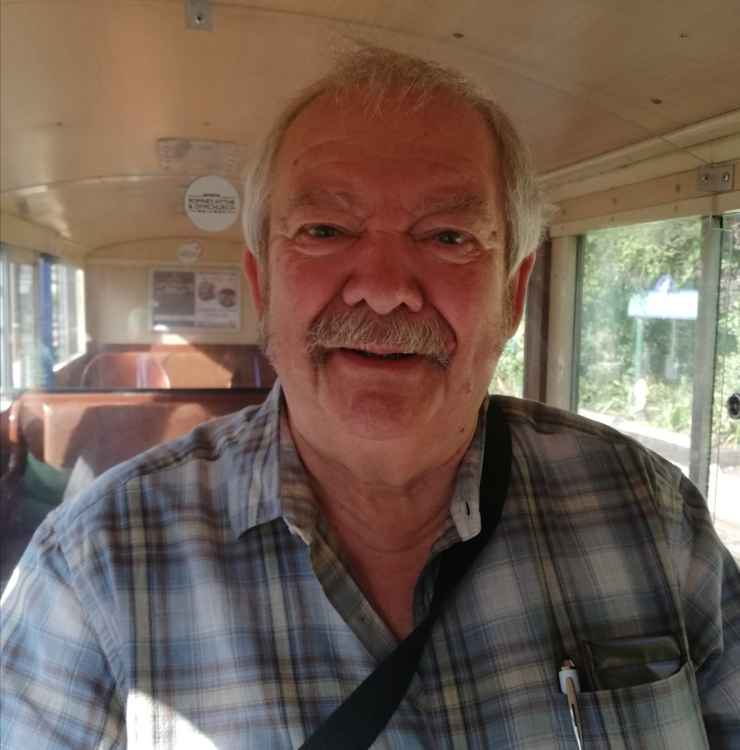

BY LOCAL HISTORIAN, KEN HOWE

It is hard to imagine that a small town like Teddington would have had much to contribute during the 2nd World War but that was not the case as we shall see.

When Neville Chamberlain’s grim words announced that we were at war with Germany on 3rd September 1939, the nation was taken by surprise.

After the affirmation of the Munich agreement, it seemed that “Peace In Our Time” had been achieved.

Teddington, along with other towns in Britain, tested its air raid sirens, formed its Home Guard units and generally tried to act as if we were ready for war. The initial fears died down as we entered the “phoney war” period. Life returned almost to normal and complacency seemed the biggest danger.

The year turned to 1940 and the long awaited troubles struck. The French line collapsed and the British professional army, the British Expeditionary Force was in a trap by German Panzer divisions and forced back to the coastal town of Dunkirk.

The BEF dug in around the sand dunes awaiting the next onslaught. Dunkirk did not have much of a harbour left after heavy German bombing and the many sunken wrecks and the shallow waters off the coast meant that the heavy naval ships could not get close to the shore to evacuate the stranded troops.

In London, Admiral Ramsey was put in charge of an emergency evacuation which the Admiralty hoped would liberate 30,000-40,000 soldiers. He quickly realised that smaller craft were needed to get into the shallow waters and ferry troops to the big ships. A decree went out to all boat yards along the Medway, Solent and the Thames for suitable craft to be commandeered.

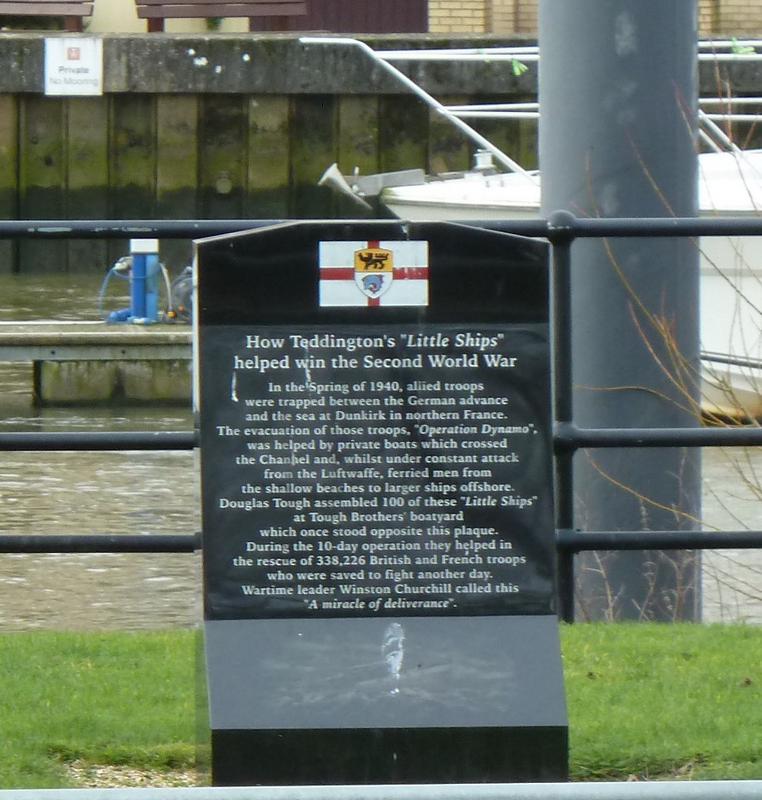

At Teddington Lock, Douglas Tough of Tough Brothers received a cable from the Admiralty, ordering him to collect all suitable boats on the Thames and in view of the shortage of experienced seamen with a knowledge of the Channel, some of their owners also.

He assembled more than 100 craft and towed them to Ramsgate where they were fitted out for the Dunkirk crossing. A couple of the boats had to be returned as these were the permanent homes of persons who had been away at work at the time Douglas Tough called. One pet cat almost went on the mission.

Between 26th May and 5th June, under constant enemy fire, the small ships sailed in and out of the shallow waters, taking load after load of soldiers off the beaches and to the comparative safety of the heavy ships anchored offshore. By the time the operation was finished by extensive enemy fire, 332,226 British soldiers and about 58,000 French had been rescued to fight another day.

There were losses and about 100 of the “little ships” failed to return. However at the 50th anniversary of the evacuation, Bob Tough sailed the cruiser “Minnehaha”, a vessel that his father had found at Ramsgate with her wheelhouse virtually burnt out but with her chart drawer intact. I am pleased to say that son John Tough skippered the boat in the 2015 crossing.

The first enemy bombs to fall in this area were on Tudor Avenue, Hampton on 24th August 1940. They caused much damage to housing but there were no casualties. As the blitz gathered pace, the concentration in the area increased, particularly as enemy aircraft returning home followed the route of the Thames and unloaded any spare bombs on whatever looked a likely target.

Teddington’s worst night was 29th November 1940 and is still remembered by some elderly residents. The raid started at 7.20 pm that night and altogether 257 separate incidents were recorded in the Borough’s Incident Book. It was the night when high explosive bombs rained on Teddington and Bushy Park; over 100 delayed action bombs were amongst the fall.

The Willoughby Hotel in Church Road took a direct hit. It was a busy night with the pay out of the Christmas Loan Club.

The landlord, Frank Tomlin, and his family and several customers – in all seventeen people – perished at the pub which was never rebuilt. Half of Argyle Road was demolished. The Baltic Timber Yard in Stanley Road was hit and the blaze lit up the sky.

The Baptist Church in Church Road was also bombed and set alight. More deaths occurred in Railway and Tranmere Roads and in Shacklegate Lane, fourteen people died.

Families from Walpole Crescent were evacuated to the supposed safety of the air-raid shelters at the National Physical Laboratories but unfortunately one of the slit trenches sustained a direct hit with six fatalities. In total forty-three people lost their lives that night with a further ten hospitalised with serious injuries.

From the very start of the war, extensive activities were taking place at the Admiralty Research Laboratories. There, a young scientist from Hampton Wick called Peter Wright perfected a “degaussing” system which was to protect our shipping from magnetic mines. In fact this proved to be so successful that not a single naval ship at Dunkirk fell victim to a magnetic mine. He further developed this system to make midget submarines foil German magnetic detectors on the seabed and in this way, our X-Craft submarines were able to penetrate the enemy defences in Norwegian fiords. In 1944 they attacked the German pocket battleship “Tirpitz”, crippling her and effectively putting her out of the rest of the war.

Sometime after the war, Wright was called up by MI5 and became the scourge of enemy agents during the cold war. Dissatisfied with his pension arrangements, he later went to Australia to write his memoirs and is now universally known as “Spycatcher.”

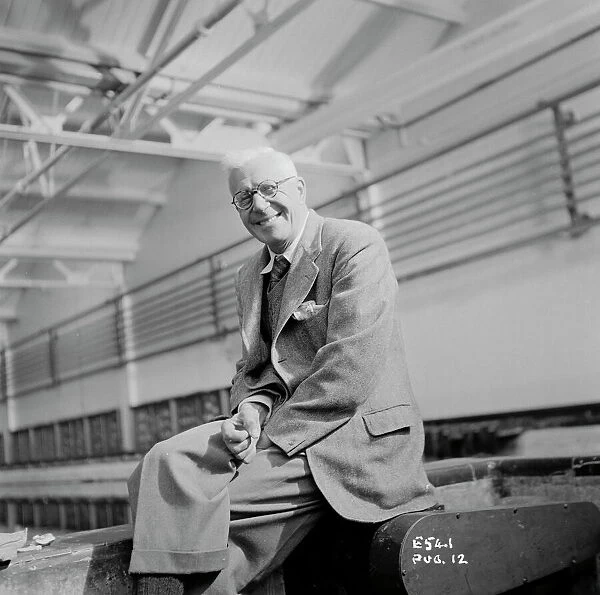

Meanwhile at the neighbouring National Physical Laboratories, another scientist was working on a completely different project. Barnes Wallis was developing a special type of bomb to breach the dams of the Ruhr valley, thus depriving the Germans of a good part of their hydro-electric power, so valuable to their steel production.

Wallis was already an established aircraft designer for Vickers-Armstrong at Weybridge; he had already been heavily involved with the R100 airship and the Wellesley and Wellington bombers. He reckoned that by disrupting Germany’s steel production, the war would be shortened by several months.

The “spherical bomb – surface torpedo” was to be dropped into the water at low level, where it would then skim along the surface like a seaside pebble to its target, the dam.

It would then sink to the base of the dam and explode. The technology for the “bouncing bomb” as it became to be known was developed at the Alfred Yarrow tank of the William Froude Laboratory of the N.P.L.

This was put to devastating effect on 17th May 1943 when 617 Squadron – The Dambusters – attacked and breached the Mohne and Eder dams and severely damaged the Sorpe dam.

Sadly, the raid did not cause as much disruption as Wallis had hoped for but it gave Britain a tremendous morale boost at the time. Unfortunately recent works at the N.P.L. have removed the Froude Laboratory and the William Yarrow tank is now a car park

The pounding that London took during the blitz caused many employers to see if they could continue their operations somewhere more safely out of London.

One such firm was Shell Petroleum who had set up their sports and social club – Lensbury – by Teddington Lock. Shell moved all of their key personnel to the Lensbury Club and this continued to be their headquarters for the remainder of the war.

During this period, their sports fields were ploughed up as part of the “Dig for Victory” campaign and the cricket pavilion became the Air Raid Wardens’ post.

Bushy Park, which had played host to many allotments in the First War, was again utilised for food production.

There were also several temporary buildings set up along Chestnut Avenue in between the trees to provide office space for workers whose London offices had been bombed out.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, America entered the war.

A new but raw army was transported across the Atlantic to be trained to carry the fight to Germany. The 8th US Army Air Force arrived in Bushy Park on 9th July 1942 and established their HQ.

Local legend had it that the massive convoy of vehicles arrived at Bushy due to a navigational error, for which the Americans had a reputation, when in fact they should have joined the existing American base at Bushey near Watford. If it was an error, then it was an easy one to make as the nearby railway station had been called “Teddington and Bushey Park.”

The camp was named “Camp Griffiss” after Lt. Colonel Townsend Griffiss, the first American casualty of the war in Europe. Ironically he was shot down in “friendly fire” by a Polish RAF pilot.

The camp’s codename was “Widewing” reflecting the wingspan of the giant bombers. One of the provisos of setting up the camp was that when hostilities were ended, the camp would be restored to parkland.

The base was not actually vacated until 1963. The establishment of the camp began a sometimes fragile alliance with the local population; the womenfolk looked on them as knights in shining armour whereas the menfolk coined the mantra “Overpaid, oversexed and over here!”

It was therefore surprising that the camp commander called a public meeting. Many thought he would explain the protocol of his soldiers mixing with the young girls of the town and the precautions taken to maintain a happy relationship.

In fact the reason he had called the meeting was to report that a number of young girls had been caught trying to break INTO the camp and he was seeking the assistance of the town to prevent this.

The maintaining of morale was given a very high priority in wartime. An interesting development took place in Richmond in 1941. The Mayoress, Mrs Phoebe Leon, was anxious to be able to provide a facility for ordinary people to be able to enjoy a nourishing meal at a reasonable price, within the framework of rationing. She set up several premises as eating establishments and also commissioned a series of recipes for this purpose and the concept of British Restaurants was born. News of the venture reached the Ministry of Food who were much taken with the idea and arranged for Mrs Leon to extend the scope of activity to the whole nation.

Soon every town in Britain had its very own British Restaurant. In Teddington, the premises now housing Headmasters Hairdressers in the Broad Street was selected and continued in use until 1946.

From June 1941 bombing raids on England continued but on a much reduced scale. The devastation caused in the blitz of 1940 still needed to be cleared up and building materials were in short supply.

Very often an unexploded bomb would be found amongst the debris and this would delay clearance until the offending bomb had been dealt with. Between 1942 and 1943 there were only about thirty raids on London and only one of these reached Twickenham.

Early in 1944 General Eisenhower decided to move SHAEF Headquarters (Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force) to Camp Griffiss. This was to be his base for planning the D-Day invasion on the beaches of France.

Eisenhower did not want to be based in London as he was worried about heavy bombing and also the potential distractions of London nightlife on his soldiers.

Certain ladies of the night moved into the boarding houses in Teddington to be close to the GIs and it was a problem for the local constabulary to keep the situation under control. Whilst the General was looking for suitable accommodation for himself, he stayed at Bushy Park Cottage in Park Road and it was necessary to vacate this house before he moved in. He eventually went to Telegraph Cottage on Kingston Hill.

It must have been impossible to keep such an operation secret and it was necessary to deploy huge camouflage nets over the lakes, the Diana fountain and the main Chestnut Avenue to cover up any landmarks visible to the German aircraft.

As there were now about 8,000 troops stationed in and around the park, the chances of keeping the base out of enemy eyes were slim.

On 6th June 1944 the D-Day landings took place on Normandy beaches. Despite some minor setbacks, the operation was largely successful. The assault took place on a section of coastline that had no natural harbours and the German High Command did not think that the Allies would be able to mount an attack there as there would have been no way to support frontline soldiers without heavy armour.

However the NPL had devised what were known as “Mulberry” harbours, a series of interlocking artificial harbours which were towed across the Channel, pieced together and then sunk in situ to prepare for tanks and other heavy armoured vehicles to be put ashore.

The logistics of supporting an invading army depend very much on maintaining a fuel supply and the NPL came up with the solution by providing “PLUTO” – the PipeLine Under The Ocean.

In August two complete pipelines were laid from the Isle of Wight to France and these continued to operate at full capacity until the end of the war.

Back in England, Teddington and elsewhere was seeing the attacks of the Reprisal weapons – the V1 and V2. The first V1 hit Holmesdale Road.

Further bombs landed on Normansfield Farm and Bushy Park.

Another demolished the Pope’s Grotto Pub in Twickenham.

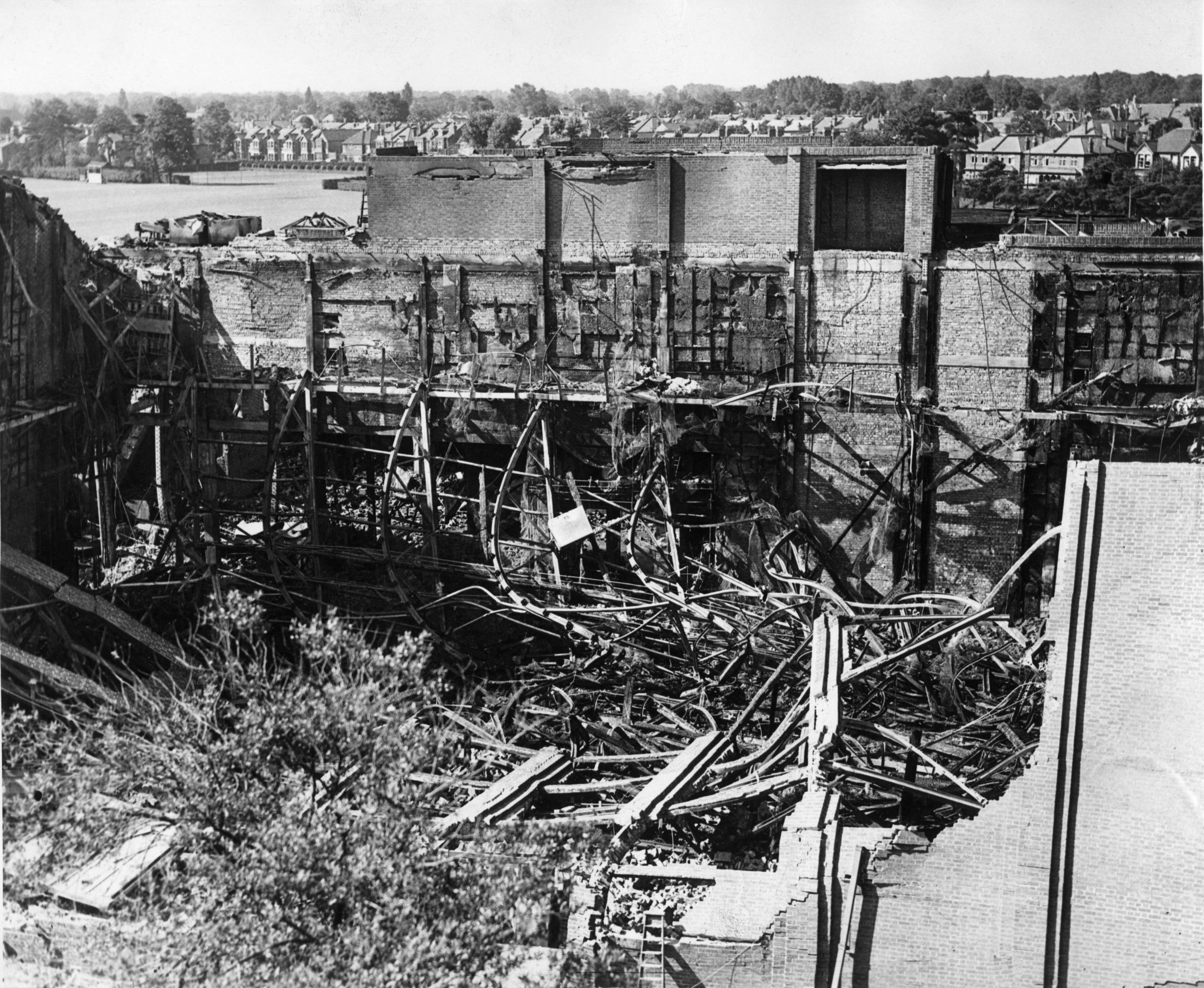

On 5th July a V1 struck the Warner Bros Film Studios in Broom Road. The bomb hit a 2000 gallon fuel tank which dispersed and ignited. The production head, “Doc” Max Salomon, along with Henry Brayfield and Elizabeth Roe were killed instantly. Employees from Toughs boatyard maintained a steady hosing on the bunkers containing the Warner Bros Film Library and succeeded in saving the film store.

On 24th July a further bomb fell on Argyle Road, already severely bombed in November 1940, causing damage to varying degrees to over 1000 houses. There were eighty three casualties including nine fatalities that night. Argyle Road was never rebuilt.

The final bomb that fell on Teddington was a V2 that hit the railway embankment behind 59-61 Fairfax Road, leaving a 40’ wide crater.

Then it was all over and the massive task of getting back to normal started.

The Borough of Twickenham statistics show 161 people killed and 275 seriously injured, 654 properties destroyed, 762 properties seriously damaged and a further 29,000 in need of repair.

Tomorrow: The full amazing story and photos of Bushy Park’s vital role in WW11